John's notebooks gradually changed their emphasis from the underlying physics of cyclotrons to more specific engineering problems relating to the Birmingham machine. One hitch arose from the fact that the heavy copper tubes and bell-casting carrying the dees had to be removable for cleaning and servicing. They were to be mounted on a carriage with strong steel wheels which had to be pulled straight back until the dees were clear and then guided round a bend into the limited area available within reach of the 10-tonne overhead crane needed to handle it. Wheels cannot easily be placed on axles such that they can move in a straight line and also keep stable when going round curves and this is dealt with in cars by turning the wheel on the inside of the curve further than that on the outside, in an arrangement known as Ackermann steering. John looked up how this was done and, working straight onto a page of his notebook, plunged into its mathematics. He then produced the drawings for his own version and finished the entry by writing down a list of the materials needed for his specification.

John's notebooks gradually changed their emphasis from the underlying physics of cyclotrons to more specific engineering problems relating to the Birmingham machine. One hitch arose from the fact that the heavy copper tubes and bell-casting carrying the dees had to be removable for cleaning and servicing. They were to be mounted on a carriage with strong steel wheels which had to be pulled straight back until the dees were clear and then guided round a bend into the limited area available within reach of the 10-tonne overhead crane needed to handle it. Wheels cannot easily be placed on axles such that they can move in a straight line and also keep stable when going round curves and this is dealt with in cars by turning the wheel on the inside of the curve further than that on the outside, in an arrangement known as Ackermann steering. John looked up how this was done and, working straight onto a page of his notebook, plunged into its mathematics. He then produced the drawings for his own version and finished the entry by writing down a list of the materials needed for his specification.The notebooks improved in appearance slightly once his right arm was out of its sling, but quickly deteriorated again. John was so busy that he was ready to try anything that would save him time. When the first Biros (ballpoint pens) appeared on the market, John abandoned his fountain pen and from then on never willingly wrote with anything else although the new pens were quite expensive. Writing was indeed quicker but as he wrote more quickly, his writing, which before had been merely untidy, rapidly became illegible to anyone without considerable practice in reading it.

When the new academic year started, John started a course of lectures to undergraduates on electrostatics and electronic valves partly based on the work he had done in STC. In those days a lecturer was always accompanied by a laboratory technician who sat on a stool during each lecture ready to help with demonstrations. The department had a small Van de Graaff electrostatic generator, giving perhaps 100,000 volts and John liked to introduce a bit of pantomime by facing the class while standing on a thick block of insulating paraffin wax holding the output terminal, while the technician tiptoed up behind him and held a hand over his head, making all his hair stand on end. He also had a metal rod that gave noisy sparks when brought near an earthed laboratory tap. The current was in fact minute and harmless and after the demonstration, John quoted the motto: "It's the amps not the volts what kills yer".

Work also began on preparations for a synchrotron, much larger and even more expensive than the cyclotron, and designed to accelerate particles to even greater velocities. Professor Oliphant brought some Australian postgraduate students to Birmingham to help with its design and construction. To support the work, he applied for a grant of two hundred thousand pounds. The grant was refused, and one hundred and forty-one thousand pounds offered instead, which upset the Australians because they had thought that the original request was rather low anyway. John went down to the staff dining room with them and they had a gloomy lunch, grumbling about the meanness of the authorities. Towards the end of their meal they couldn't help but notice the increasing noise from a group of zoologists at a nearby table, which was now strewn with empty beer glasses. So John went over and asked them what they were celebrating and they told him that they had just succeeded in their application for £ 20 to buy rabbits!

The end of the war gave John his public voice back. Freed from the secrecy imposed by the war, he was given permission by the Admiralty to publish some of his work on velocity modulation, presenting a paper in Paris in 1946, and writing another a year later. He began to do a fair amount of public speaking on research in industry and atomic research. After the United States had started to test atom bombs, he included talks on 'Peace and the Atom Bomb' to try and convince people that nuclear weapons were immoral and were potentially far more dangerous than many people imagined. Supporting his country during the second world war did not mean that he had deserted his pacifism and the more he thought about nuclear weapons, the more worried he became. He didn't think that people understood the speed with which the destructive power of the bombs was being increased. He could already see the first stages of an arms race developing and foresaw this running out of control. Later on, as more was discovered about the lethal effects of radioactive fallout, he became even more concerned.

Family life was developing according to plan now that it had been given a fair chance. A school was found for David who was now four and a half, to which John took him in the mornings on the back of his bicycle before going on to the University. Soon after starting, David was moved up to join a class of five to six year olds, where, he told him mother, he did "comperlicated sums". John loved answering his son's questions, and, determined to avoid giving him any false information, began to buy reference books including a second-hand encyclopaedia.

Reinet was pregnant again, and this time there were no problems. The baby was due in February, and Joe and Peggy Robertshaw, who were now living in the Lake District, offered to look after David for the period surrounding the birth. I was born on 3rd February 1947, and was given the names Margaret Heaver after both my grandmother and grandfather. It was a bitterly cold winter, and David went down with pneumonia on the same day. The Robertshaws' doctor refused to move David to hospital in case the ambulance got stuck on the snow-bound country roads, and so Peggy did all the nursing. However, the doctor was prepared to try a relatively new drug, penicillin, and came out every day to give him injections leaving a supply of pills, which had to be given four-hourly, day and night. John travelled all night to get up to Cumbria to help, and finding that Peggy had been up for the two previous nights tending David and giving him his pills at the right times, took over the next night. David improved quickly and soon it was necessary to get up in the night only occasionally to stoke up the fire.

David's illness lent extra impetus to renewed efforts to get a house with a proper garden. John replied to an advertisement for a house in Richmond Hill Road, Edgbaston, less than a mile from the University, using University headed paper. The seller of the remains of a lease on the house received a huge pile of applications and when he started opening them, one of the first was John's. He was a clergyman who had been connected with the University, and the idea of someone who worked there taking the house appealed to him so that was the application he accepted. By borrowing from his Uncle Edward, John was able to take the eleven-year lease on the property and in May the family moved in; it did not take him long to pay his uncle back.

Number fifty-three was a large Victorian house in an imposing position at the top of a hill, its white rendering greyed by Birmingham smoke. Its shabby condition didn't worry the Fremlins in the slightest, and they furnished it as best they could, with the added difficulty that furniture was still rationed. Reinet painted orange boxes for shelves and treacle tins for lamp bases and made rag rugs out of scraps of material to ameliorate the icy floors in the bedrooms. John took the greatest delight in finding cheap furniture at auction sales; not many people were interested in the big old pieces of furniture that tended to turn up in auction rooms because they simply would not fit in small modern houses, but John and Reinet could easily fit such monsters into their spacious rooms. The size of the house was not such an advantage when it came to heating it: the family spent their first winter cowering in the kitchen and one of the living rooms, which was all they could afford to keep warm. Before the end of 1948 John put layers of transparent sheeting over the windows as temporary double glazing, and diligently sought out and stopped all draughts. Bruno Ferretti, who also worked in the Physics Department, had been lodging with the Fremlins in Moseley and moved with them. He and his wife stayed for the first few months helping wherever possible to make the house habitable. Part of the house divided off neatly to form a small flat, and two Australians, John and Claire Gooden moved in almost immediately. John had come over to supervise the building of the synchrotron, and the Goodens and the Fremlins became close friends.

Other Australians from the University also visited the Fremlins frequently. (There were eventually enough Australians to form a cricket team to take on the English for several summers.) Soon after John and Reinet moved in, John went out and bought a mowing machine and other tools and brought them back on his bicycle. Thus equipped, the Fremlins organised a 'gardening' party at which their visitors helped mow, dig, prune, clear out the overgrown pond and so on, and then Reinet gave them all a meal outside. After that successful start, callers were liable to find a paint brush or a pair of garden shears thrust into their hands when they arrived, but this did not seem to put them off and Reinet became conveniently convinced that they preferred doing something useful to sitting around. John then partly filled in the pond to make it shallower, built a concrete-lined sand pit, hung a swing on a branch of a large cedar tree and started a vegetable garden. Vegetables were not grown for long, however, as neither John nor Reinet enjoyed growing or eating them enough, but over the years they produced a steady flow of fruit to be preserved in Kilner jars. John and Reinet started a habit of taking a stroll round the garden on pleasant evenings to 'view the estate', which lasted until they were both in their seventies.

As the cyclotron approached completion it continued to absorb more and more man-hours, and the cyclotron team sometimes had to stay until eleven in the evening sorting out new problems as they arose. Original work was being done by everyone who was involved through the sheer necessity of overcoming each successive hitch. Research students, including John's first PhD student John Walker, and even third year undergraduates all got their share of the hard work and the excitement. But in October 1947, John got a break from it in the form of a trip to the United States. Professor Oliphant had obtained a grant to allow John and John Gooden to visit the main particle accelerators in the States, starting with Berkeley where the first large cyclotron (about the size of the Birmingham one) had been working for some years, and a very much larger one had just begun to work. John, having a PhD, was given a first class berth on the Queen Elizabeth and $14 a day for expenses, while his friend, with some years of technical experience with the Australian armed forces but no post graduate qualification, was given a second class berth and $10 a day. John rearranged the daily expense allowance to $12 each but couldn't do anything about the berths - he did not think travelling first class was of any advantage anyway, finding second class passengers more interesting.

They spent nearly two months in the States, moving between various cyclotrons and synchrocyclotrons under construction, travelling mainly by rail and occasionally by air. The big cyclotron at Berkeley had been opened for inspection and the dees withdrawn. The vacuum tank was so deep that they could walk around inside by stooping a little. They did not know how radioactive this would be, but knew that the Berkeley staff habitually went into the tank when servicing equipment and were confident that they would not have taken serious risks. This assumption may not have been justified: by that time radiation sickness due to the immediate fallout from the Hiroshima bomb had been recorded, but nobody knew about the long-term risks of leukaemia and the still longer-term risks of other cancers. John did know something of the risks of mutation and, aware that he might be going to be in some radioactive environments, had suggested to Reinet that if they were going to have a third child it might be a good idea to start it before he left England. Reinet had agreed, but he had left before there was time to know if they had been successful although from previous experience, they had no reason to believe that they could not time a pregnancy accurately.

Between their visits to particle accelerators, the two physicists fitted in a certain amount of sight-seeing. John had a weekend at the Yosemite valley in California, staying in one of the little cabins to be found spaced out among the trees on the valley floor. He decided to go up to Glacier Point where a great bonfire was sometimes lit at night and pushed over the edge of a vertical cliff to fall down burning to the valley below. The walk to the top was some miles, the upper part being covered with snow. He found no human tracks at all in the snow, only one track of a bear that had followed the path for perhaps thirty metres. At the top he had a look at the bonfire waiting to be lit, and while doing so, saw another man coming up from the path on the far side. He turned out to be a Brazilian, but one who spoke good English and, like John, had seen no human footprints anywhere. They spent a few minutes deploring the fact that not one of the 1500 Americans in the valley camp had had the energy to come up, and then went back down together. They both felt happier for the company when they met the bear tracks again.

John broke another journey with a visit to the Grand Canyon. The local train that took him there had a large supply of literature written in glowing terms and giving the impression that you could see straight down half way to the centre of the earth, so that the first glimpse of the real thing was disappointing and it took a little time to appreciate the vast reality. There were mules for getting down to the bottom, but John preferred to walk. The track started under snow that disappeared after he had descended about 200 metres. The rest of the way was easy with a series of three fairly flat 'steps' separated by steep slopes. The last flat area near the Colorado River had tall Saguero cacti and other hot climate desert plants. John had been told that he could either stay in an expensive hotel at the bottom, or rough it in a cabin and get meals at a tea house. He opted for roughing it, which he did in a solidly built wooden cabin with a ready-laid fire and a good supply of logs. The next day he climbed to the top and caught the evening local train back to the main line to join the East-bound express.

During one of their later cyclotron visits, John discovered a radio enthusiast who had been in contact with a Birmingham amateur. An arranged time was set for John and John Gooden and their two wives to go to the houses of the respective radio hams so that they could exchange messages. Claire was ill at the time with jaundice and could not manage the journey across Birmingham on the back of a motorbike. When reporting on this event forty years later for this book, John and Reinet remembered it differently. Reinet believed that they had had quite a lengthy conversation but John thought they had managed only a very few sentences. He remembered asking Reinet if anything had happened yet. The answer "no" told him just what he had hoped: their next baby was on the way.

The trip ended with a couple of days in New York when the two Johns walked along Broadway and went up the Empire State building. John had far more luggage than he had come with by the time they boarded the Queen Mary. All the Americans he had met had been extraordinarily generous: worried by the difficulties of bringing up children in 'communist' Britain, they had pressed quantities of good quality second-hand children's clothes on him, and when he had begun to refuse any more contributions for lack of space, he was given extra suitcases. The Americans were also horrified by the continuing food rationing in Britain and were sure that the British must all be malnourished but it was more difficult for them to give extra food to carry onto the boat.

Just before John had left for the United States, he had been appointed a lecturer. He had understood from Oliphant that he would be taking over in the final year laboratory from Dr A A Dee who had been in the department for a long time and who was about to retire. John thought that it would be more diplomatic to ask for help and advice than to walk straight in and take over, but his attempt at a polite request misfired and the incumbent said that he would rather retire immediately than work under John, that he was still in charge and all the decisions would be made by him. John saw no alternative to accepting his position as an assistant without complaint until Dr Dee did retire two years later, and then immediately updated most of the experiments. It would seem that either John or Dr Dee had misunderstood Oliphant's intention.

After starting teaching, John was unable to put so much time into the cyclotron and the work was roughly divided. W I B (Wibs) Smith took over the main responsibility for the radio-frequency power supply operation and control while John retained the responsibility for the mechanical and engineering structures. At the same time, Oliphant took on Dr Geoffrey Fertel, a very capable all-rounder, as John's second in command. With this help, and the usual hard work of the rest of the team, the Birmingham cyclotron had been progressing well in John's absence in the USA and shortly after he returned it had reached the stage where everything could be switched on, but as predicted, there were a number of problems to iron out, which occupied the team for the next six months.

A continuing theme in John's research work had been one of finding and dealing with leaks. To operate correctly the main tank, made from a bronze casting, had to be airtight so that as good a vacuum as possible could be maintained inside it. Apparently bronze is difficult to cast without bubbles in it, so this one was cast at the bottom of a twenty foot column of liquid bronze, which apparently created a tank with a perfect finish. However, once the Birmingham team began to drill holes in the tank for electrodes and holding bolts, they found that the whole tank was in effect a sponge surrounded by a gas-proof surface layer. Each time a hole was drilled, air would find its way into the sponge and emerge at some unexpected point inside the tank. To cope with this phenomenon, the team took each screw out, filled its hole with low-vapour-pressure grease and then returned the screw. If no grease was squeezed out by the screw, it was taken out and more grease added to the hole on the assumption that the first dab of grease was insufficient to fill the wandering hole inside the bronze. As John had found as a research student, finding the leaks became progressively more difficult and he included the following ratio in his paper 'Cyclic Accelerators':

d(human effort) is very large!

d(particle energy)

He suggested that cyclotron operators might have to sacrifice the ability to get the highest energies out of their machines by giving up looking for leaks while the remaining air pressure inside the tank was slightly higher than would be ideal. The work of getting the vacuum in the Birmingham tank to an acceptable level took nine months. Meanwhile, Dr H A H Boot had been building a control room, a complex affair for looking after the multiple functions of the parts of the cyclotron. For example, a dozen or so water-cooling circuits were needed, the failure of any one of which would allow some part or other to melt, so each water circuit had its own tap and a pressure gauge connected to a warning light in the control room.

The summer of 1948 found Reinet heavily pregnant. At last the cyclotron team had managed to get the cyclotron airtight, after finding and stopping fifteen leaks in one month, so John and Reinet threw a party to celebrate. This went on quite late, and the next day Reinet installed herself in a deckchair in the garden and dozed, while I played. The pond that John had filled in earlier to reduce its depth to a few inches to make it safe for small children was concealed from the main garden by a patch of raspberries, and as she dozed, Reinet heard a little splash. Hearing nothing else, she eventually decided to go and look, thinking that I might be playing with the water and might be frightened if I were to fall in. To her horror, she found me lying quite still, face down in shallow water. Her immediate reaction was to haul me out by the ankles, aware as she did so that my body was lifeless. She stood helplessly for a few seconds, still holding me by the ankles, wondering what she was supposed to do next, when the water ran out of my lungs and I started gasping and crying. John arrived home to find me perfectly alright after a warm bath, but Reinet still very shocked. That very evening, still amazed that a child could actually drown in such shallow water, he erected a child-proof fence around the pond. As is always the way with disasters, he and Reinet then heard numerous stories from other people of toddlers who had been drowned in a few inches of water. After falling, a small child always opens its mouth for a big intake of breath in order to cry before making any attempt to get up, and this procedure is apparently not changed just because its face happens to be under water. As this happened when I was only sixteen months old, I have no memory of it and have never been aware of any fear of water.

My sister Jane Heaver was born on 8th July 1948, which left Reinet with her hands extremely full. Although John and Reinet were not spending much money on furniture for their house, they did see the need for one of the new washing machines that were coming onto the market, and promptly bought one. Friends from the University were still helping with restoring the house and looking after the garden and at the same time providing Reinet with some much-needed adult company.

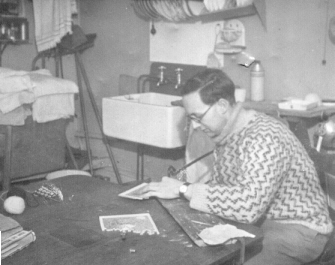

Geoffrey Fertel became a special family friend. He helped chop down a tree in the garden making a chopping tool head to fit on a borrowed electric hammer and then taking the device round and round the tree. When John told him that he wanted David to have a train set for Christmas, he helped to design a track to take a purchased clockwork locomotive and coaches, and he and John set to work in the Physics Department workshops to do all the bending and welding needed to make several dozen pieces of track that could be screwed together. Geoffrey spent Christmas day with the Fremlins. When David was first setting the railway up, it was found that another pair of points dividing the other way would be useful, and Geoffrey rushed off to the University and made the extra item there and then.

So the whole family was affected by the tragedy that occurred soon after Christmas, in January 1949. Geoffrey had been working on a condenser that would stand the high electrical discharges from the cyclotron and his latest version was being tested. The main power supply could be turned on from the control desk on the floor above it, and Geoffrey was puzzled by some loud sparking noises when it was switched on. So he turned it off and went down into the pit with a ladder from which he could watch the likely source of trouble in the coil running at eleven thousand volts and forty amps, keeping in contact with the control room by radio. The control room staff switched off until he called up to say he was now in position and could they switch on. When the electricity was switched on, he said something to the effect of 'it is alright, I see where it is.' There was an odd noise and he didn't answer a question as to what it was, so the power was immediately switched off and Oliphant and the control-room staff went down to find him collapsed on the floor, with burn marks both on the ladder where his feet had been and on the live lead to the main oscillator on which, for no known reason, he had clearly put his hand. John was up in a lab at the time and was called down by telephone. He took turns with someone else to give artificial respiration, which they continued in the van that took them to hospital, but Geoffrey could not be revived. At the inquest, a verdict of accidental death was recorded and the foreman of the jury made a statement absolving Professor Oliphant of any blame.